Breaking free of the limitations of modern-day software development

.png)

.png)

Part 2 – The Unavoidable Pitfalls

As a team of architects, consistently experiencing some of the primary issues in software development, we wanted to really understand what was fundamentally causing this. It’s not obvious with the constant parade of new technologies, patterns, and architectures that keeps getting pushed on us claiming to solve all our software problems. What is clear, however, is that most in the industry recognize the same problems (Refer to Part 1).

Wanting to truly understand these problems set us on a journey to discover why so many software projects were suffering. What ultimately emerged was a recognition of what we later called the Four Unavoidable Pitfalls of software development:

- Technical debt

- Architectural rigidity

- Falling behind the technology curve

- Loss of system knowledge

While these are the catalysts for deterioration, we also recognized that there is a root cause that underpins them and essentially brings them into existence... and that is: code. More specifically, lots of code.

The reality is that code has a certain weight to it. It can be likened to building blocks, which developers create and connect together to realize the functionality and architecture of an application. But, with only two hands and a keyboard, each developer is limited to moving only a few blocks at a time - they can only lift so much. To make matters worse, these blocks are often connected to other blocks (coupled), meaning that moving one may require others to be moved, which may in turn require some others to be moved, and so on. Depending on how well the system is designed, one change can very quickly lead to changes across the entire system.

“Code is not an asset. It’s a liability. The more you write, the more you’ll have to maintain later.”

Therefore, as a rule of thumb, the larger a system gets, and the more code that makes it up, the more difficult it becomes to make significant changes. It just requires too many lines of code to be altered (and tested) in the available timeframe for it to be deemed worthwhile. It is in this predicament that other detrimental forces begin to manifest and persist. If taken to its logical end, it becomes clear that no matter how well a system is architecturally designed, at some point the sheer weight of code makes it practically impossible to make meaningful changes.

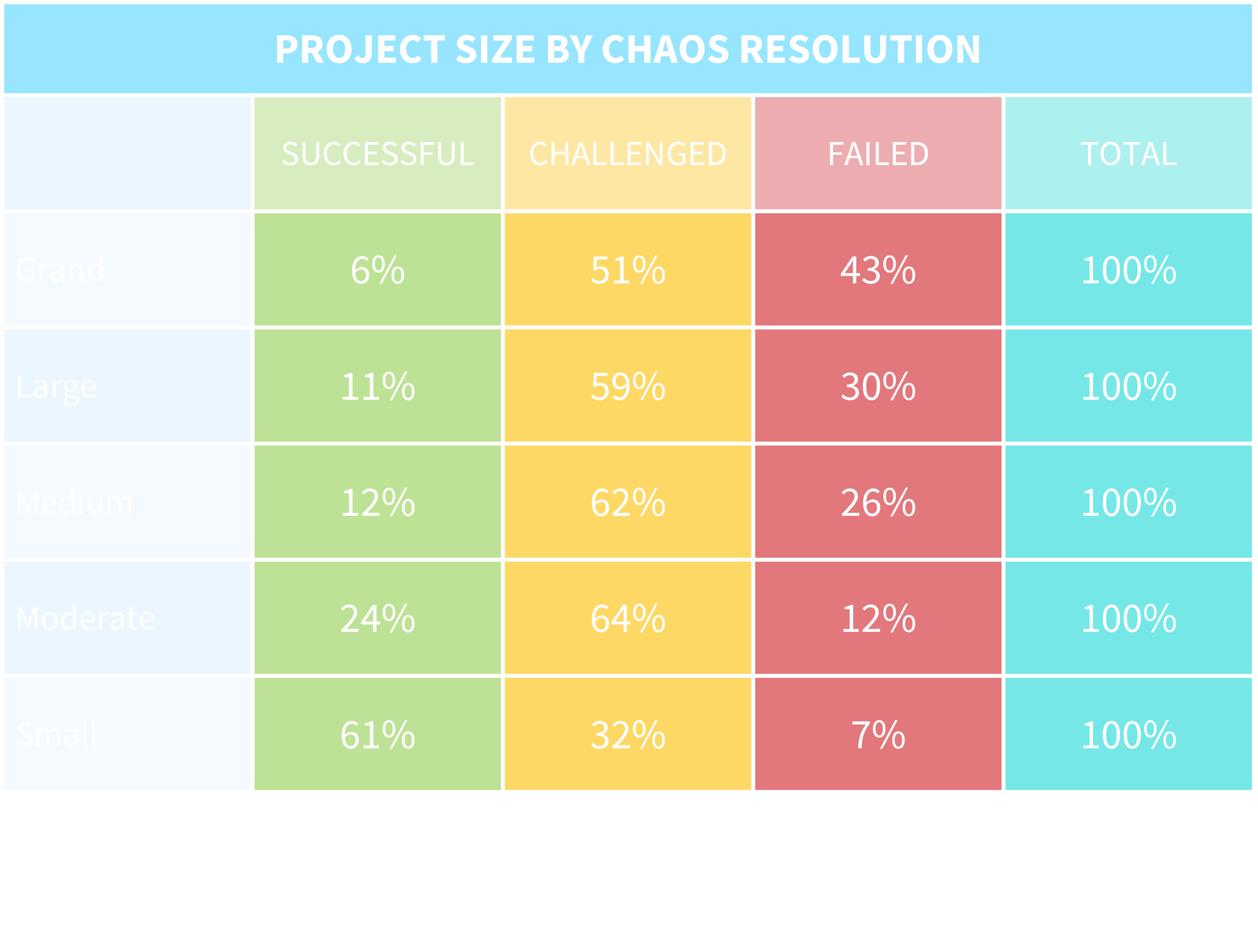

The table below is taken from the Standish Group’s CHAOS Report of 2015 which assesses project outcomes from a broad database of software projects. From the report, “It was clear from the very beginning of the CHAOS research that size was the single most important factor in the resolution of project outcome.” Success in this context is defined as On Time, On Budget, and with satisfactory results:

The Four Unavoidable Pitfalls

1. Technical debt

Technical debt in software development points to the hacks, shortcuts, inconsistencies and often chaos that accumulates in a codebase over time. The metaphor frames this “cruft” (as Martin Fowler2 calls it) as a form of financial debt which incurs interest over time - the interest being the additional effort needed to make changes and add new features.

Software systems are highly prone to the build-up of technical debt. With each change to the system, the developers are often inadvertently (and sometime deliberately) creating inconsistencies, eroding the design, and increasing software entropy. Extrapolated over time, the effects of this make each new change harder to achieve.

If not actively resisted, the internal quality of the codebase will continue to deteriorate. It’s the progression towards the “big ball of mud” or “spaghetti code” that every seasoned developer knows too well. The ultimate result is a codebase that is hard to understand, has unexpected side-effects to most changes, and becomes so difficult to maintain that a rewrite is the only viable solution.

Battling technical debt is very frustrating. In modern software practices, the only answers to mitigating the rate at which it grows is by actively tackling it: maintaining a good architecture with appropriate separation of concerns, having stringent pull-request and code reviewing processes, and spending the time needed to address known technical debt and design issues.

Unfortunately, there are significant costs to this, and businesses don’t always have the budget, patience, or appetite for developers to spend time addressing technical debt. Building features and enhancements are what keep the lights on after all. Teams are often given no choice but to build on top of existing hacks, driving them deeper into debt. This compounds over time and eventually cripples any attempt at making significant changes. Ironically, even though actively tackling technical debt is essential to ensuring that the system remains maintainable – the very thing that enables the team to create new features and enhancement for the business in the future – business tends to block it as they see it as an expense with no real return.

2. Architectural rigidity

The purpose of a system’s architecture is to meet its non-functional requirements – e.g. performance, security, scalability, maintainability, flexibility, etc. In code, it’s the patterns that “glue” the business logic and technologies together, often making up over 70% of the codebase. In larger systems, architecture is almost impossible to get right up front, and will invariably need to change. Evolving requirements and growing complexity quickly exhausts the existing architecture’s ability to manage them. The team is then forced to choose between refactoring entire architectural patterns or being bogged down by the existing constraints. Typically, the former is only an option if the system is still small and the business can absorb the cost.

This architectural rigidity is dangerous for software systems. For instance, a key role of any architecture is to manage the complexity of the system. As the system grows, new features connect to existing features, which are connected to other features, and so on. The complexity grows exponentially. If the team is unable to shift the architecture to accommodate this complexity, it quickly devastates their ability to change and extend the system going forward - things are too interconnected and there are just too many factors to consider. Making changes in one place leads to breakages in others. Productivity becomes paralyzed.

The software industry aims to control complexity through architectural patterns such as Microservices, CQRS, layering, etc. It’s helped along by design patterns, principles such as SOLID, and design methodologies such as DDD (Domain Driven Design) - essentially anything that lowers coupling, improves cohesion, and separates concerns. When used appropriately these patterns provide effective ways of dealing with the complexity required by many modern software applications.

The challenge, however, with many of these architectural patterns is that they are expensive, time consuming, introduce trade-offs, are difficult to coordinate across a team, have inherent complexity in them, and are difficult to implement correctly. Their subtle nuances are often misunderstood by even veteran developers, and the number of poorly implemented instances tend to outweigh the number of well implemented ones.

It rarely feels justified to invest so much in an architecture unless the team knows they will need it. By the time that they do, the rigidity of what exists can make refactoring the system an impossibly large task. In addition, the fact that the software industry has no well-defined engineering standards means there is no formal consensus of which pattern to use where.

3. Falling behind the technology curve

When a new project is started, most teams will choose the latest established technologies available to them. We developers love playing with the latest shiny toys, after all. However, within as little as two years, it is often the case that the industry has moved on and those technologies are considered outdated. To some degree, the same can be said for many architectures, patterns, and best practices (e.g. The progression from Monolithic, to SOA, to Microservices).

Falling behind is inevitable. The reason is simply that too many lines of code are written against the API of that technology. In the early days of a project, the team may be able to switch technologies over a period of weeks. Later, however, the cost is too great for the business to absorb, and the team is stuck with what they have. Even worse, in the case where the developers chose the wrong technology and realized this too late, the situation can jeopardize the entire project.

The problem with being stuck with any particular technology is three-fold. First, the tech may not support certain non-functional requirements (e.g., cannot be deployed to the cloud, is nonperformant, has security issues, etc.). Second, it may prevent the upgrade of other technologies in the stack where a dependency exists. Last, outdated technologies can cause the best talent in the business to become frustrated and leave, while simultaneously hiring good talent becomes harder.

When a system passes the threshold for feasibly being able to change or upgrade a technology, modern practices really offer only two options: the rewrite or the strangler pattern. Microservices can help break the rewrite up, as each microservice can be rewritten separately. In practice, however, it is rare that all the microservices get upgraded and the result is usually a cacophony of different technologies that the team now needs to understand.

Unfortunately, the strangler pattern has the same shortfall. Teams rarely complete the upgrade across their entire system and, instead of different technologies and patterns spread across microservices, the different patterns live alongside each other in the individual applications. Systems with several different architectural patterns and technologies spread about are sadly not uncommon.

Regardless of how one tackles the problem, technology upgrades (as well as any fundamental architectural changes) are tedious, frustrating, and incredibly risky endeavors, often incurring an immense cost and setback for the business.

4. Loss of system knowledge

When a developer leaves the team, they take with them all their knowledge of the system’s design, architecture, and patterns. More significantly, they take all their knowledge of why those decisions were made in the first place. In the case of a key developer (e.g., the architect or technical lead), this can be a massive blow for the team, as their lack of understanding soon leads to bad design decisions, confusion, and a tendency for technical debt to skyrocket.

Correspondingly, every time a new developer joins there is usually a period of weeks to months before that developer has acquired the necessary knowledge of the system to be able to start adding value to the team, at least in terms of their cost as a resource. This is especially true on larger and more complex projects. Their lack of understanding of the architecture, design, and business is crippling - leading to bugs, mistakes, and hours spent rummaging through code trying to reverse engineer the intentions. There is rarely a document that explains the design, its intentions, and how the architecture is implemented.

Even where there is little to no staff attrition on a team, the developers often begin to forget the intricacies of the older parts of the system. Larger, more complex codebases are typically harder to reason about and without some kind of blueprint of the design, an immense amount of time can be spent trying to understand where and how a change should be made. Often, while not truly understanding the design and its intentions (or where the current design breaks down and should be changed), developers accidentally cause unintended issues, and incur technical debt that is costly down the line.

On the surface, the seemingly obvious answer is for teams to create comprehensive documentation of their systems, providing both a high-level abstraction as well as details where needed. However, aside from being enormously expensive to create and often executed poorly, the main issue with documentation is the fact that it becomes outdated the moment any of the underlying code changes. An outdated document is often misleading and therefore quickly ignored.

Agile teams recognize this and rather chose to incorporate knowledge sharing into their processes (e.g., pair programming). The aim is to mitigate the effects of an individual leaving because in theory their knowledge has been distributed to other members of the team. Still, this approach to knowledge transfer is often unreliable and can lead to a significant loss of productivity from your most knowledgeable people. The information shared in sessions is rarely transferred accurately and bound to quickly fade into vague memories of old discussions and ideas.

Ultimately, all modern approaches to organizational knowledge retention are flawed or at best bound to some hefty compromise. The result is that most projects have strong key-man dependencies on one or two individuals, have no clear blueprint of their system, and where documents have been created, most are outdated, adding little to no value whatsoever.

.png)