Breaking free of the limitations of modern-day software development

.png)

.png)

Part 3 – Solutions & Mechanisms

While the prospect of the unavoidable pitfalls of software development casts a gloomy shadow over the software industry, the first step toward solving a problem is recognizing it and understanding it. As most engineers know, the next step is to envision the ideal solution, before considering how it will be achieved.

Therefore, we had to imagine a world where the root of each pitfall (refer to Part 2) would be addressed, and determine what that ideal would look like. It was important, however, that these ideals were constrained by the realities of modern software – that it’s built by people and therefore must be limited by the capabilities and preferences of the human mind. Ultimately, we imagined a world where:

1. Code has no weight

Imagining code without weight is to imagine being able to change thousands of lines of code as easily as it would be to change ten. Shifting designs would be effortless, which would prevent developers from deliberately creating technical debt, and make it easy to fix existing design flaws. It would mean that teams could keep their codebase consistent and standardized, remain agile and flexible to changing requirements, and prevent the majority of technical debt, design erosion, and entropy that creeps into most systems.

2. Architecture is free

If architecture were free, teams could choose their architecture on purely technical trade-offs, not cost related. Teams could ensure that they have patterns and architecture that is able to handle the growing complexity and specific non-functional requirements of their project, without investing months of time into setting it up and maintaining it.

Combining this ideal with that of code without weight would theoretically make it trivial for developers to change and evolve the architecture as and when they needed. The dangers of architectural rigidity could be avoided completely.

3. Technologies are interchangeable

Technologies and the patterns that interact with them could be upgraded or swapped out completely, regardless of project stage or how large the codebase has become. This would prevent projects from falling out of maintainability or being stuck on inadequate or unsupported technologies. It would prevent systems from becoming what most developers call “legacy”.

4. Systems are self-documenting

What if design and documentation happen at the same time, in the same activity? That the documentation was intrinsically related to the underlying code design so that it always provided a true representation of it. It would mean that a blueprint of the system would be available to all developers, at all times – true to the underlying code.

Developers would be able to move freely between projects, without jeopardizing their deliverables, or having to spend months before adding value – the design intentions clearly documented, and the risk of losing knowledge hugely mitigated. It would be important that this documentation is in a format easily understood by its consumers (e.g. visual models).

Mechanisms

These ideals are seemingly far-fetched, and one has to accept that they may never be a realistic possibility in their entirety. We live in the real world after all. But what if there was a way to get us closer to them? How would this work? Would it be practical and solve more problems than it creates?

As we scoured the market, looking for platforms or products that could bring us closer to these ideals, it initially seemed that low-code platforms could provide answers. Low-code platforms abstracted application builders away from the code and into visual models and configuration settings. But, when it came to building bespoke, core-business applications, we found that there were fundamental flaws to the low-code approach.

The visual abstraction layer prevented developers from controlling the underlying architecture or easily customizing functionality. It propagated strong vendor lock-in, and visual models have their limitations in describing complex business logic. These drawbacks invalidated the approach for the kind of software most companies were (and still are) demanding in today’s market. While we believe low-code has its place, it is clear why the approach hasn’t taken over the industry.

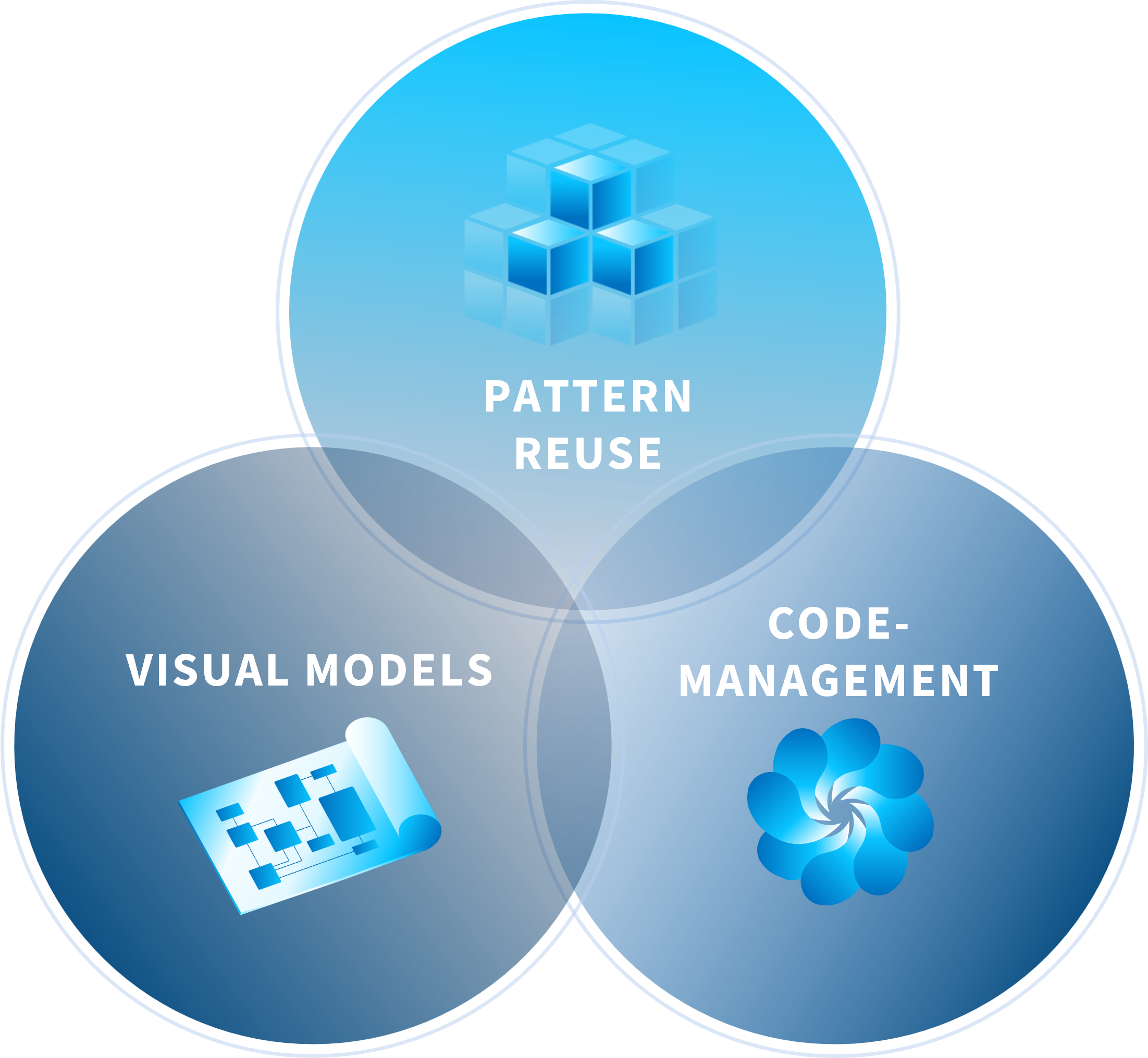

Further research and experimentation led us to many other products and methodologies (e.g., MDA, code-generation, opinionated frameworks, and many others). What we found was that certain mechanisms, when combined, had the potential to be highly effective at achieving these objectives:

1. Pattern Reuse

Code reuse is standard practice in today’s software world (consider frameworks, packages, and package managers like npm, NuGet, etc.). However, pattern reuse is almost non-existent. The reason is because each instance of a pattern is different and varies just enough to make abstracting it into a framework (or even a base-class) impractical. Yet there is a pattern that connects each instance. Architects and senior developers explain it to their team when they show them their reference architectures or examples of how to implement use cases. The fact is that most architectures are essentially a set of patterns that are repeated throughout the codebase.

Pattern reuse is the ability to turn these patterns into artifacts that can be reused within projects and across the same or even different organizations. For it to be practically possible across an entire application, it would require some form of metadata to be used by a code-automation system to realize each unique instance of the pattern. Turning this capability into an artifact that can be shared is the key to enabling the ideal of a free architecture.

For example, a team may design a powerful set of patterns that enable the DDD (Domain Driven Design) methodology. If they turn this pattern into a reusable artifact, they would make all further instances of this pattern (which may include interfaces, factories, repositories, and specification patterns) cost-free. Furthermore, they could take it to their next project, or share it with another team, giving them the ability to have this powerful architecture without “paying” for it.

By extrapolating this idea across all the patterns that make up most modern software systems, we can see how it could be possible that developers could pick and choose their architectures based purely on technical trade-offs, rather than the cost. However, for pattern reuse to be practically possible, we need the mechanisms of code-management and visual modelling, as described in the following sections.

2. Code-management

Going back to our analogy of building blocks and the weight of code, if developers can only move several blocks at a time, then code-automation (or code-generation) is the ability to move thousands in a second. After all, automation is to time what compounding interest is to money. Code-automation is by no means a new concept. But, over the last two decades, it has developed a bad reputation for being unwieldy and dangerous – and for good reason. This was particularly propagated by tools continuously generating enormous, non-human-readable files, several thousand lines long, that would frequently be regenerated and would overwrite any customizations that the developers may have needed to make. And the need to customize is inevitable in real world applications.

The safer alternative which has become quite popular is the once-off generation approach, also known as “scaffolding”. Because files are generated on creation, developers can customize the code without constraint. But, while the approach does give a brief acceleration, the code still falls under the maintenance of the developers. It therefore adds to the weight of the codebase and the generation system offers no further benefits.

Having extensively used systems like these ourselves, we understood the immense frustration that they can cause, but it was also clear to us that there was massive value in the approach – particularly when code is continuously being updated – if only the pain could be removed.

Code-management is a term we coined to represent a practical alternative to traditional code-automation approaches. Essentially, it is the generating and updating of code files by understanding them in the same way developers do – as code documents. It is a continuous approach, allowing updates to be applied to existing files, that gives developers the ability to effortlessly configure or disable the automation system at a granular level (e.g. to customize the implementation of a method in a file that is otherwise under automation). This approach brings the best of both worlds into a single solution. Where once-off scaffolding cannot change the pattern after it has been generated, and traditional continuous code-generation cannot be customized (it keeps overwriting), code-management allows both. The developers and code-automation systems can then work within the same code files. It also follows that this should generate and maintain code in the same way that the developers would have done if they did it themselves (i.e., it should not “look” generated).

This approach could allow developers to control patterns and entire layers of an architecture with the ability to escape the automation systems in the exceptional cases where a pattern doesn’t meet a unique requirement. Since changes to the code patterns can be done in one place, the number of instances that are managed would therefore not increase the weight of the code in the system, practically achieving our ideal of code that has no weight.

Of course, this approach is limited to code that follows a pattern, otherwise it would not be automatable. The good news is that the majority of architectural code (including most technology-oriented code) is typically very patternized.

3. Visual Models

Using visual models to describe software design can be incredibly powerful. It compresses information into visual formats that the human mind can quickly interpret and digest (e.g., entity diagrams, workflows, service contracts, etc.). Methodologies such as MDE (Model-driven Engineering) and MDA (Model-driven Architecture) make use of visual models to represent software domains. By following these concepts where they make practical sense and diverging where they don’t, visual models can provide a practical way to describe and document a system’s design in the same activity.

If combined with code-management and pattern-reuse in a practical way, they can be immensely powerful tools in software development. It could ensure that the documented design of the system is true to the underlying code that realizes it, thereby meeting the ideal of self-documenting the application.

Using visual models at the right level of abstraction is key to ensuring that their use remains practical. We believe this to be at the contract level, which is concrete enough to have a direct correlation with the underlying code but is abstracted enough to keep it simple and digestible. Implementation subtleties are probably best left to be described in the actual source code. From our own experience as well as that of so many others, we don’t believe that visual models represent a practical way to replace code altogether. As we’ve discussed in regard to low-code platforms, and particularly in their attempts to get around this, the approach has too many shortcomings.

For the human mind, source code is still one of the most expressive and powerful tools available for controlling technologies and describing business logic in software. It would therefore be important that visual models are only used where they are superior to code in describing a particular design concern.

.png)